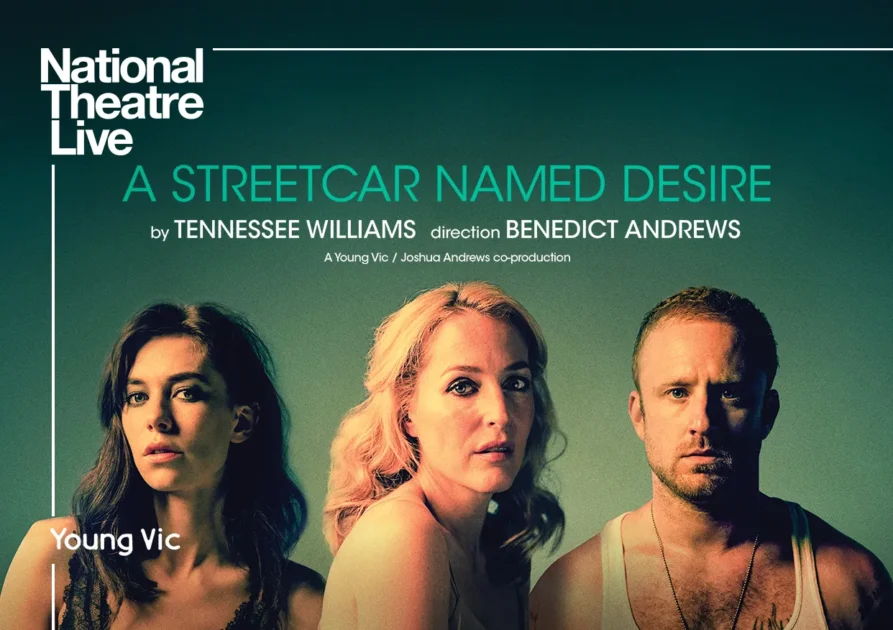

My mum said she hated the film A Streetcar Named Desire. Despite the title being a little long in the tooth, I’ve never seen it, and I kind of love this new angle of letting us at home get the theatre experience. From visionary Australian director Benedict Andrews (Una, Seberg), this critically acclaimed production was filmed live during a sold-out run at the Young Vic Theatre in London in 2014. Now returning to Australian cinemas June 19, 2025, with powerhouse casting including Gillian Anderson (Sex Education), Vanessa Kirby (Fantastic Four, The Crown), and Ben Foster (Lone Survivor), the stats are impressive. After recently covering another Encore screening with David Tennant, I’m fascinated by how these productions translate to the screen.

Skip to a Specific Section

Film Data:

- Cast: Gillian Anderson, Vanessa Kirby, Ben Foster

- Director: Benedict Andrews

- Production: Young Vic Theatre (2014)/Filmed Live | Thanks to Sharmill Films for providing the screener

- Genre: Theatre Production/Drama

- Australian Release: In Select Cinemas June 19, 2025

- What is A Streetcar Named Desire about? Fading Southern belle Blanche DuBois arrives at her sister Stella’s New Orleans apartment, where brutal realities collide with desperate illusions under the volatile presence of Stanley Kowalski. As Blanche’s fragile world crumbles, she turns to her sister Stella for solace – but her downward spiral brings her face-to-face with the brutal, unforgiving Stanley Kowalski.

Benedict Andrews’ Vision: When Australian Theatre Meets Williams’ Brutality

The production design immediately grabbed me, staging with the audience surrounding an open apartment set complete with working stairs, bed, kitchen, and that iconic non-functioning faucet. It’s like peering into a voyeuristic dollhouse where privacy doesn’t exist. The bare-bones scenic construction enables the story to stand alone without the extra frills usually found on more traditional sets, and honestly, this stripped-down approach amplifies every uncomfortable moment.

As soon as I heard “Stella,” I instantly thought of that Seinfeld episode where Elaine screams “Stelllllllllaaaaaaaaa” while doped up on painkillers. But this production quickly erased any comedic associations. Andrews’ directorial choices create this inescapable tension; there’s nowhere to hide for characters or the audience.

Ben Foster’s Stanley: Animal Magnetism Meets Toxic Masculinity

Stanley’s entrance is a masterclass in character establishment. That prolonged beat when he first sees Blanche, and she looks back, the blocking creates this electric triangle of desire, danger, and inevitable destruction. Foster brings this unsettling charisma to Stanley that makes you understand exactly why Stella stays, even as your skin crawls watching his volatile mood swings.

The poker scene breakdown showcases brilliant sound design and lighting transitions. When Stanley flips out and smashes the radio they were singing and dancing to, the production utilizes dramatic lighting shifts, those green washes during emotional transitions that announce scene changes through color psychology rather than traditional blackouts. It’s phenomenal how they darken to those sickly undertones when the mood plummets.

Gillian Anderson’s Blanche: Performance Within Performance

Blanche immediately reads as that family member who steals everything you have, acts superior constantly, yet still needs to lean on someone she considers beneath her. Anderson kept her commanding presence, and you can see how she’s maintained that magnetic quality that makes her bragging about high-end belongings feel both desperate and entitled. But as the production unfolds, the layers peel back to reveal someone desperately clinging to genteel fantasies while reality crumbles around her.

The moment she makes a play for Stanley while Stella’s outside, pure manipulation masked as Southern charm. Stanley’s line, “I never met a woman who didn’t know how good looking they were,” cuts through her performative facade like a blade. Fortunately, Stanley initially resists, but you can feel the inevitable collision building through every interaction. Anderson captures that duality perfectly – someone who thinks Stanley’s wife (Stella, who’s pregnant but hasn’t told Blanche yet) deserves better, while simultaneously trying to seduce him herself.

When Violence Becomes “Romance”: A Streetcar Named Desire

The domestic violence scene hits different in this intimate staging. Stanley punches Stella after the radio incident, Blanche takes her upstairs, and then, this is where the production gets really dark. Stanley doesn’t remember what happened. Classic gaslighting behavior.

“You can’t just beat a woman and then call her back!” Blanche’s outrage feels authentic, but then Stella sneaks down later in her nightdress to comfort him. The cycle of abuse plays out with horrifying clarity. Stella makes excuses about poker games and women; she’s been enduring his rage attacks since their wedding day, and she even cleans up his mess afterward.

The most chilling moment in A Streetcar Named Desire: Stella describes their relationship as “being in the dark with one another.” The lighting design literalizes this metaphor, bathing scenes in shadow and artificial warmth that feels suffocating rather than romantic.

Streetcar Symbolism: Desire as Destruction

When Blanche explains the streetcar named desire rhetoric, and Stanley overhears her calling him “a basic animal,” the thematic weight becomes crystal clear. She’s all about poetry, sensibilities, romance, and respect, everything Stanley represents, the opposite of. But if he’s the streetcar, then desire itself becomes this unstoppable force that destroys everything delicate in its path.

The flash-forward to Stella’s advanced pregnancy while Blanche still lives with them creates this pressure cooker atmosphere. Despite wanting to take her sister away from Stanley’s toxicity, Blanche remains trapped in the same cycle. The red wash over the stage as she falls for Stanley’s friend provides the only moment of genuine hope, a cinematically gorgeous staging that uses color temperature to signal emotional shifts.

Technical Excellence in Intimate Spaces

The sound design in A Streetcar Named Desire deserves particular praise; every line reading feels amplified by the acoustic properties of the round staging. You catch whispers, hear breathing, and feel the oppressive New Orleans heat through ambient sound layering. The soundtrack crescendos during emotional peaks without overwhelming the dialogue, creating this immersive soundscape that traditional proscenium productions often struggle to achieve.

The costume design subtly reinforces character psychology. Blanche’s deteriorating finery contrasts sharply with Stella’s practical domesticity and Stanley’s working-class authenticity. Every wardrobe choice supports the narrative without screaming for attention.

This production captures everything powerful about Tennessee Williams’ masterpiece while creating intimacy with deeply uncomfortable subject matter. The domestic violence feels more real, the sexual tension more dangerous, and Blanche’s mental deterioration more heartbreaking when you’re this close to the destruction. Now I absolutely have to seek out the original 1951 film, because despite my mum insisting it was an awful story, I agree completely and love it for exactly that reason. Sometimes the most brutal truths make the most compelling cinema.

It’s a brutal, beautiful examination of desire, delusion, and the lengths people go to survive their own realities. The theatre-to-screen format preserves the live energy while making this exceptional production accessible to audiences who can’t make it to Brooklyn or the West End.

Verdict

A Streetcar Named Desire is rated

4.5 Streetcars named trauma out of 5

We have more stage-related things to watch: Art Kabuki / Inter Alia (National Theatre Live)