I’ve started catching up on films I missed when they first dropped, and The Rule of Jenny Pen was high on that list. Turns out, waiting was worth it. From its opening moments, the 2024 New Zealand psychological horror hooks you in and refuses to let go. What surprised me most, though, was hearing a line I’ve had in my Instagram bio for years, “The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places,” spoken aloud in the film. Until now, I never knew it came from Hemingway. That unexpected discovery deepened my connection to the story’s themes of resilience and ruin.

Rush vs. Lithgow: The Unlikeliest Grudge Match in Elder Care

⚠ Spoiler Warning

This review discusses character motivations, the antagonist’s methods of terrorizing residents, specific scenes of psychological abuse, and the climactic confrontation. The ending outcome is revealed but final details are kept vague.

Film Data For The Rule of Jenny Pen:

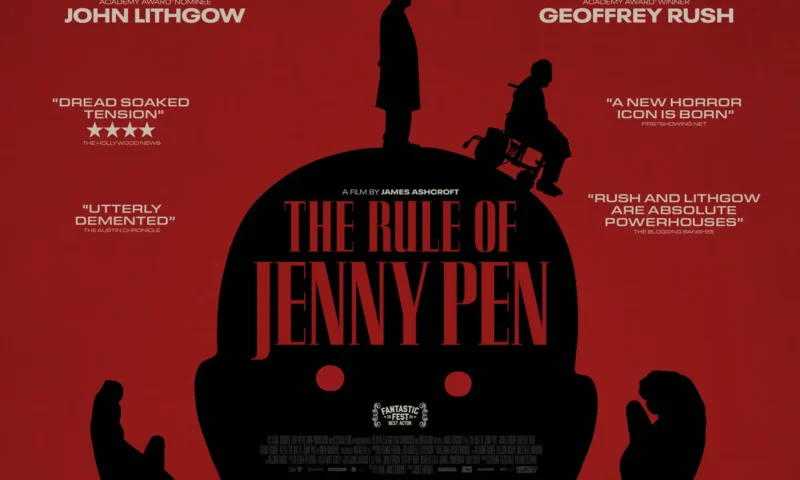

- Directors of The Rule of Jenny Pen: James Ashcroft (Coming Home in the Dark)

- Writers: Eli Kent, James Ashcroft, Owen Marshall

- Stars: Geoffrey Rush, John Lithgow, George Henare, Maaka Pohatu

- Genre: Psychological Horror/Thriller

- Runtime: 1 hour 44 minutes

- Distributor: IFC Films & Shudder | North America, UK’s Vertigo Releasing |

- Light in the Dark Productions

Blueskin Films - Based on Owen Marshall’s short story, who also stars (as an extra).

- Head to the Official Website for more information.

I went in blind, and only now, post-watch, did I look up the synopsis or bios. The film unfolds like a trap you’re not aware you’re walking into.

Geoffrey Rush plays Stefan Mortensen, a judge ousted from power and stuffed into a care facility after a stroke leaves his body weakened, but his legal mind razor-sharp. Right out of the gate, we see him tear down repeat offenders in court with intellectual ferocity and moral bite, laying into a woman who allowed a predator near her five kids. He’s principled, sharp, and frankly, terrifying in his authority.

Rush plays Mortensen as a lion in a paper cage: frail on the outside but prowling underneath. His decline is shot with brutal realism. Anyone who’s watched a loved one go through cognitive deterioration will feel that hollow familiarity in the editing choices, staccato cuts, fragmented time jumps, and framing that squeezes him tighter as the story goes on. He’s a tragic figure: part-hero, part-ghost of his former self, and painfully aware of both.

A Monster in Plain Sight – Lithgow’s Demented Turn

Enter John Lithgow as Dave Crealy, a former staffer turned permanent resident due to a decades-old bureaucratic oversight. He’s the wolf in the nursing home, preying on residents through a game known as “The Rule of Jenny Pen,” using a decrepit child’s doll as both weapon and mouthpiece. The Rule of Jenny Pen is the overarching villain, and we love it like that.

Lithgow leans hard into the predator role. Every dismissive chuckle, every breathless asthma wheeze, every cold glance as he manipulates his surroundings, there’s no question Crealy is the villain here. What’s maddening is how long it takes the institution to acknowledge it. Despite visible bruises and outbursts, Crealy floats under the radar, his violence dismissed as a symptom of mental decline. It’s chilling.

“You really do seem like someone entirely absent of empathy.”

Quote from the film The Rule of Jenny Pen

In a moment that chills the blood. Creely is mandated as not confused. He’s calculated. And the worst part? Everyone looks the other way.

The idea that he’s been living there since before 1968 is dropped with such casual horror that it’s easy to miss. That kind of clerical mishap doesn’t just suspend disbelief; it shines a light on real-life institutional apathy. He’s been on the walls of this place longer than anyone realizes, and now, he’s using that familiarity to exert unchecked control.

Visual Dread and Institutional Horror

The film’s atmosphere does heavy lifting. A grimy amber palette cloaks everything in unease, while deliberate vignetting draws the eye to off-kilter horrors lurking in the frame. It’s the kind of visual storytelling that punishes multitasking, blink and you’ll miss something meaningful.

Crealy’s access to every room, hallway, and darkened nook adds layers of dread. That he has keys to everything while being written off as “harmless” because of dementia? That’s real horror. The way staff continually ignore the obvious, visible marks, residents in distress, and incidents that couldn’t have happened alone amplifies the theme of systemic neglect.

Red lighting during night scenes contrasts brilliantly with shadowy hallways, making Crealy’s nightly prowls feel like miniature hellscapes. Editing choices are razor-sharp, isolating the viewer in unsettling close-ups and sonic gaps where wheezes and whispers take over.

One of the most effective tools? His asthma. It humanizes him just enough to confuse the viewer, but not enough to excuse him. The inhaler becomes a weapon, a weakness, and eventually, the key to his undoing.

Puppet Games and Psychological Warfare in The Rule of Jenny Pen

This isn’t gore-driven horror. It’s psychological warfare disguised as elder care. Crealy’s demented attachment to his puppet, Jenny Pen, is grotesque and fascinating. It’s not just a doll; it’s an avatar for his cruelty, a proxy for manipulation. The way he uses it to absolve himself, speak through it, terrorize others, disturbing, doesn’t even cover it.

The film makes you feel like you’re watching a biopic about nurse killers. That same sense of powerlessness creeps in. He terrorizes Howie, another resident, with pointed malice, not just because he can, but because it draws out Stefan. Howie becomes the mouse in this cat-and-mouse game, too afraid to speak up for fear of being pitied by his grandson. That thread doesn’t fully land, but the performance sells the conflict anyway.

And when Stefan tries to read him, whether he’s the result of clergy abuse, a neglected child, or just a bitter soul, you can see he’s not looking for understanding. He’s trying to build a legal case in his mind. He can’t turn off the judge, even here.

Aging, Justice, and That Final Verdict

This is a story about what it means to age and still matter. Stefan’s decline is heartbreaking, not because he loses his edge, but because he knows it’s slipping. He tries to fight for others, to protect, to prosecute, in a world that no longer recognizes his authority.

His bond with Howie starts with dismissiveness, even cruelty. But their arc becomes one of quiet companionship and mutual protection. Their scenes, full of poetry and silence, become emotional anchors in a plot built on mental manipulation.

The climax is shocking in its simplicity. Crealy gets outmaneuvered at last, not by brute strength, but by the one thing Stefan still controls: justice. He sabotages Crealy’s inhaler, forcing a final wheezing reckoning while the puppet dance plays out in chilling contrast. It’s earned and terrifying.

And yet, this nursing home seems to operate without basic high-alert protocols. By the end, it’s almost laughable how long it took anyone to react.

When Stefan is rolled back into the dining hall, bibbed and barely verbal, and Howie attempts a haka he can’t finish, it’s a moment of profound emotional defeat and solidarity all at once. They stopped the monster, but at what cost?

Final Thoughts | Menace, Memory, and the Unrelenting Gaze

The final scenes deliver a kind of melancholy relief. The camera pans through daily routine, laughter, snores, and shuffling games. Stefan doesn’t leave the home. He isn’t cured. But he’s free in a way that matters.

The one unresolved beat? Crealy’s backstory. A bit more insight into how he operated unnoticed for so long would’ve sharpened the terror. But between Rush’s ferocity, Lithgow’s chilling nuance, and Henare’s quietly heartbreaking role, this film transcends its occasional gaps.

It lingers. It disturbs. It stays.

The Rule of Jenny Pen

Director: James Ashcroft

Date Created: 2025-03-07 07:09

4.5