Mother of Movies usually refuses to review Yorgos Lanthimos’ films on principle: they tend to feel like cinema’s final form, and everything I write about them reads smaller than the work. Bugonia is the rare exception where I broke my own rule and brought a scalpel to the hive.

Title: Bugonia

Directed by Yorgos Lanthimos

Screenplay by Will Tracy

Based on Save the Green Planet! by Jang Joon-hwan

Distributed by Focus Features (worldwide), CJ ENM (South Korea)

Release dates: 28 August 2025 – Venice Film Festival, 24 October 2025 – United States

Review by: Mother of Movies

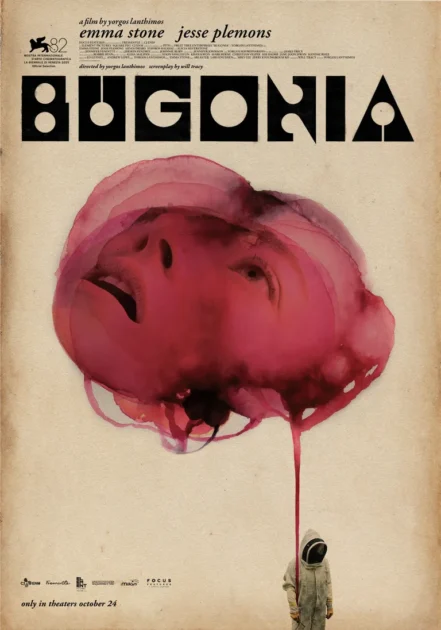

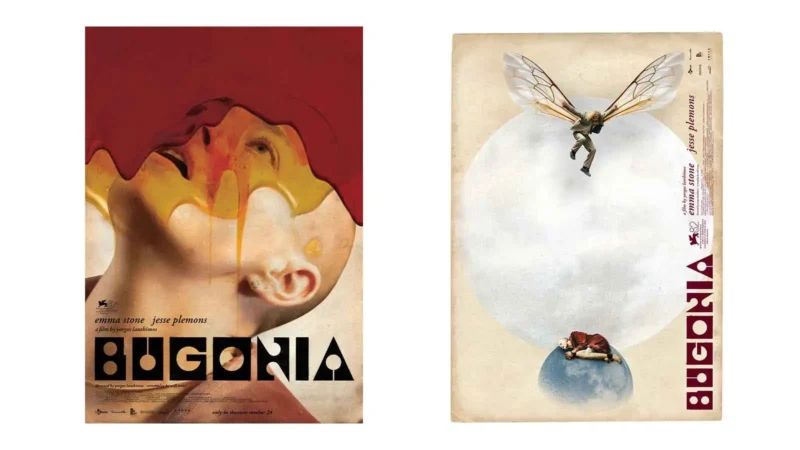

For a variety of alternative Bugonia posters (including Mother of Movies), visit the official Wallpaper store.

This review dissects Bugonia like a conspiracy theorist with a corkboard and too much red string. Major plot turns, imagery, and the final Andromedan wipe are discussed in detail. If you’d rather discover which species deserves to survive on your own, bookmark this and buzz back later.

Corporate Bees, Chemical Castration & The Cult of “Optimization”

Bugonia opens with bees and flowers, a little visual TED talk on pollination that feels almost wholesome. It’s sex without the mess: nobody cries, nobody texts their therapist after, and no one has to pretend “we should do this again sometime.” It’s nature as a clean transaction.

Then Lanthimos tilts the frame and asks what happens when humans try to industrialize that purity.

Two cousins, Teddy and Don, are in the middle of what sounds like a late‑night podcast for men who spend too much time on fringe forums. Teddy is spiralling into a cosmology where bees, industry, and shadowy “organizations” all point to a larger alien design. His solution? Discipline, denial, and the ultimate self‑own: chemical castration. He’s already done it, he claims, like a guy proudly announcing he’s deleted all social media, except this time it’s his libido.

Don, meanwhile, is unconvinced. He still has this outdated notion of maybe wanting to be with someone one day. Teddy calls that a “pain trap” and talks about harnessing neurons and being free, like a wellness guru sponsored by a doomsday cult.

Their fixation converges on Michelle (Emma Stone), a high-powered CEO in the biomedical sector. We meet her through a corporate workout montage, training, combat drills, vitamins lined up like bullets. She’s a finely tuned machine running a company that preaches “diversity” in front of the camera, then quietly reminds staff they’re “free to leave early… unless you have quotas, deadlines, or work to do.” It’s the kind of phrase you hear in real-world corporations just before the burnout stats hit the news.

Bugonia locks these threads together: cult logic, corporate gaslighting, and the human body treated as a productivity problem.

Abduction as Job Performance Review From Hell

Michelle drives home and is ambushed by Teddy and Don, masked in silver suits like budget sci‑fi invaders. She fights back hard; the choreography emphasizes just how much conditioning she’s poured into survival, but Teddy wins via syringe. They shave her head while she’s unconscious, a violation that reads as both dehumanizing and ritualistic. Teddy believes hair is how aliens contact the mothership, so off it goes. They burn it, because of course they do.

Here’s where Bugonia gets deliciously nasty: the way they handle Michelle is functionally indistinguishable from how her own company treats its workforce. She’s stripped of control, redefined as an “it,” placed under surveillance, and measured only by what she can produce, not profit this time, but proof of alien origin.

Teddy monologues about her being a 45‑year‑old executive who destroyed his community, the bees, and the world, accusing her of being responsible for everything from environmental collapse to personal tragedy. When he insists she must be an alien because the alternative would mean human systems actually did this… it lands uncomfortably close to how people now talk about “the elites.” It’s easier to call someone a lizard than admit the economy is working exactly as designed.

Michelle calmly, then desperately, insists she’s not an alien. She records the message he wants, tries to talk him down, but Teddy’s logic is bulletproof in that uniquely terrifying way: any evidence against the conspiracy is proof of how deep the conspiracy goes.

Don watches her on camera as she cries, increasingly unsure. Teddy, of course, is euphoric. He thinks he’s finally “saving everyone,” even as he’s reenacting the exact systemic violence he claims to oppose.

Industry Sells You the Sickness, Then Sells You the Cure

Bugonia folds in a quietly devastating flashback: Teddy’s mother, cancer, and a bitter line that could function as the film’s thesis;

“They sell you the sickness, then they sell you the cure.”

She dies. His world collapses. The shot of her floating, half grief hallucination, half anti-capitalist parable, connects pharmaceuticals, exploitation, and Teddy’s obsession with Michelle’s biomedical empire.

Then Lanthimos lands one of his cruellest ironies: Teddy works in the packing line of Michelle’s own company. He’s literally inside the hive he believes is poisoning the world, shipping out the very medical products he thinks are alien mind control. When he sees her photo on the wall at work after the abduction hits the news, the film quietly underlines a brutal reality: most people are complicit in systems they hate because that system also pays their rent.

The antihistamine ointment they smear over Michelle “to even the playing field” is another great bit of dark comedy. They frame it as protection against alien skin chemistry, but it is, hilariously, just allergy cream. If you’ve ever watched tech bros rebrand basic therapy as “bio-hacking,” the joke writes itself.

Bugonia is ruthless but not random. Every choice, from chemical castration to shaved hair to eclipse timing, plays like a ritualized attempt to make cosmic sense out of human pain. That’s Lanthimos’ sweet spot: trauma alchemized into absurd religion.

Andromedans, Dinosaurs & Why Humanity Gets Wiped

When the Andromedans finally arrive, the film pivots from paranoid chamber piece into cosmic checkmate. Teddy’s demand is simple: make them withdraw. Fix everything. Reverse the damage. But the tragedy is that Bugonia never lets him ask the right question.

The film strongly hints that it’s not just some “dinosaur rerun” extinction cycle. What might actually trigger the wipe is us finally noticing the pattern. Teddy’s obsession, Michelle’s industry, the bees, the sickness, once humans start to connect the threads and glimpse that there is a larger structure, the Andromedans treat it like a containment breach. Awareness becomes the apocalypse.

I love that. It’s bleak, but it’s also honest. We live in a world where every time people get close to understanding how power really operates, something conveniently destabilizing happens. Bugonia takes that vibe and scales it into cosmic horror: the moment you’re self-aware enough to ask if the food chain has a board of directors, the board decides you’re too much trouble.

Where a lesser sci‑fi thriller would turn this into a resistance fantasy, Lanthimos stays consistent: the hive corrects itself. Humans aren’t “special”; we’re just the latest failed experiment that realized it was in a lab.

Performances, Craft & That Lanthimos Stamp

Emma Stone’s Michelle is a precise weapon. She never goes for “victim” in the obvious way; she oscillates between CEO steel, survival instinct, and genuine fear. When she’s told, flatly, that Teddy simply cannot believe she’s a regular middle-aged woman instead of an intergalactic oppressor, it stings.

Teddy and Don are equally sharp. Teddy’s fervour feels painfully familiar, that mix of online radicalization, spiritual yearning, and untreated grief. Don is the film’s conscience, if only in potential. His uncertainty, his silence when he’s ordered not to speak, creates a counterpoint that keeps the movie from collapsing into pure manifesto. They’re not cartoon villains; they’re what happens when powerless people are given just enough ideology to make them dangerous.

Formally, Bugonia is textbook Lanthimos: cool, composed framing that lets the horror just sit there; tonal juxtapositions that flip from very funny to very cruel in a breath; bodies controlled and choreographed like lab animals. The corporate interiors feel antiseptic and aspirational, while the holding space where Michelle is kept is stripped, anonymous, and functional, a visual echo of how corporate culture and cult logic share the same skeleton.

The score works like a low-grade panic attack. It’s not overbearing; it hums and pulses, tightening around Michelle and Teddy as the eclipse approaches. Occasionally, it spikes into something almost religious, particularly around the flashback with Teddy’s mother, underscoring how faith and fury are welded together here. Composer Jerskin Fendrix wrote and conducted the score, performed by the London Contemporary Orchestra. It’s his third team‑up with Lanthimos, following Poor Things (2023) and Kinds of Kindness (2024).

Similar Titles – Need More Neon Cult Paranoia?

If Bugonia crawled under your skin, try any of these for similar energy:

- Save the Green Planet! (2003) – Korean cult classic where a man kidnaps a CEO he’s sure is an alien; blends conspiracy, class rage, and tragic absurdity.

- The Favourite (2018) – Lanthimos’ royal court backstab-a-thon; power games, manipulation, and women weaponised by systems they didn’t design.

- The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017) – Cold, ritualistic morality and punishment; a family trapped in a nightmare that feels both mythic and clinically modern.

- Sorry to Bother You (2018) – Corporate satire, body horror, and labour exploitation dialled up to surrealist eleven.

- Network (1976) – The original “they sell you the sickness and the cure” media satire; prophetic, furious, still uncomfortably accurate.

Yorgos Lanthimos: Filmmaker Stamp

Yorgos Lanthimos has built a career on weaponizing discomfort. From Dogtooth through The Lobster and The Killing of a Sacred Deer to The Favourite and Poor Things, his stamp is unmistakable: rigidly composed frames, dialogue that feels slightly misaligned from everyday speech, and characters trapped inside systems that claim to protect them while quietly devouring them.

He’s obsessed with constructed realities. Families as cults, relationships as contracts, monarchy as theatre, and medicine as theology. Violence in his films is rarely random; it’s an extension of rules everyone pretends not to understand. Bugonia slots directly into that canon. Corporate culture and conspiracy thinking become rival religions, both convinced they’re saving humanity while accelerating its demise.

A Cult of Bees & Biomedical Sin

Bugonia plays like a hostage thriller possessed by a conspiracy subreddit, then elevated by Yorgos Lanthimos into something sad, funny, and viciously precise. Emma Stone weaponises CEO poise against zealotry, while the film quietly suggests that the real horror isn’t aliens, it’s the way we industrialise grief.

“Bugonia plays like a hostage thriller possessed by a conspiracy subreddit,then elevated by Yorgos Lanthimos into something sad, funny, and viciously precise.” – Mother of Movies

Bugonia Is Rated

Bugonia is rated

4.5 chemically castrated cult leaders still blaming aliens out of 5

Bugonia

Director: Yorgos Lanthimos

Date Created: 2025-08-28 15:25

4.5